From family tree to network

1/6

The urban patricians of the early modern period defined themselves through political participation, economic success, and a pronounced consciousness of family lineage. As families involved in municipal governance, they had a decisive political and economic influence on their urban communities. This development can be found in many places; it also applies to Basel, where the image of the Daig (Basel’s literal “upper crust”) has become a particularly apt formulation (Daig meaning dough).

2/6

A prerequisite for the rise of these families was citizenship. Many family histories begin with the commemoration of the ancestor who was the first to be granted civic rights. In the case of the "ckdt", for example, i.e. the Burckhardt family, it was "Stoffel" who was naturalised in 1523. In the case of the Faesch family, it was Heinzmann, who acquired Basel citizenship as early as 1409. The knowledge of their own migration history was, however, quickly lost.

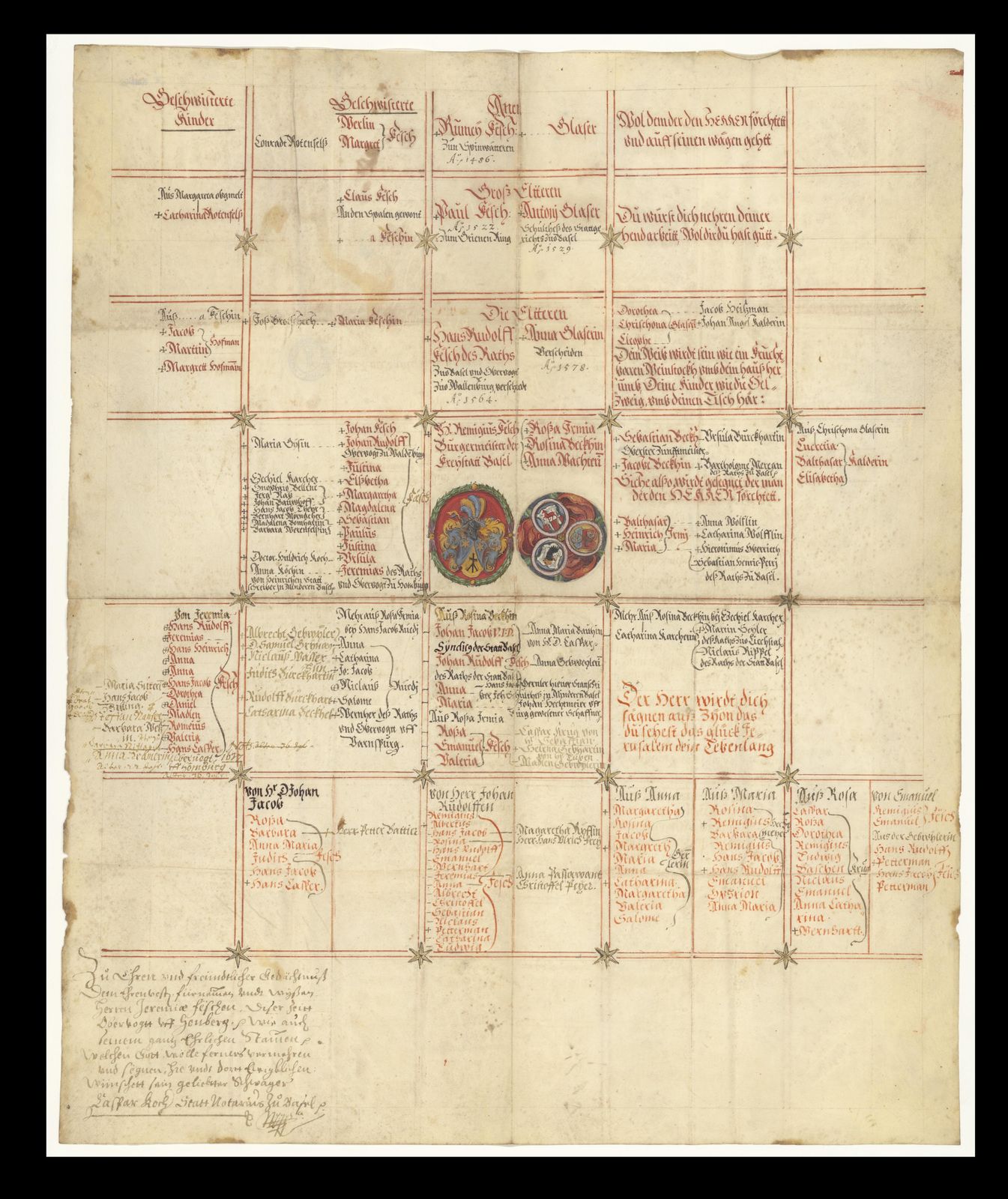

The Faesch family tree documents origin and asserts local tradition.

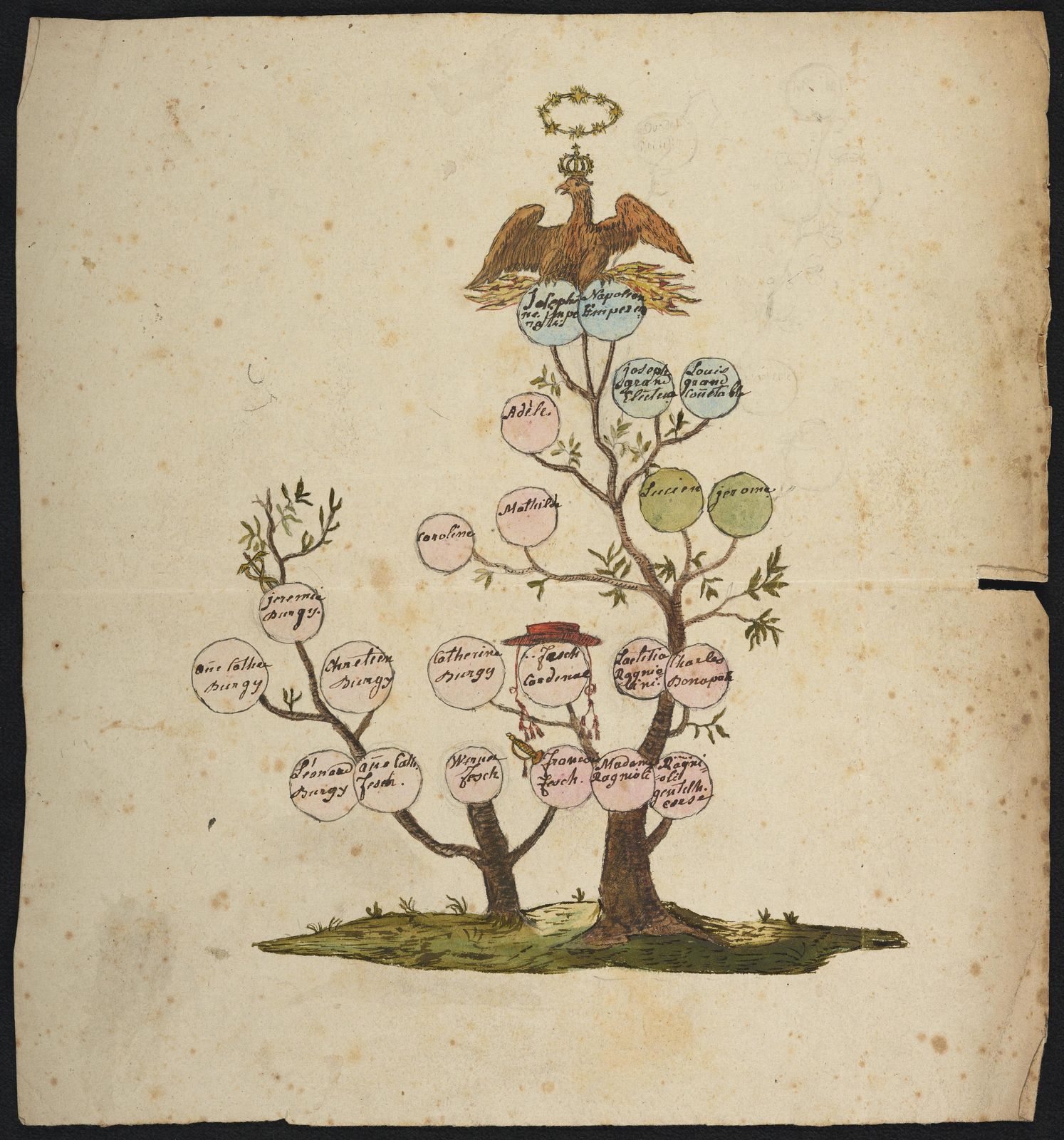

In order to preserve it, making a family tree was often useful. A common practice among aristocrats for centuries, this is how awareness of one's local roots found an appropriate expression. But at the turn of the modern era, bourgeois families also began to present their origins and history in this way. Such documents are legion in Basel family archives – including those of the Faesch family, down to Napoleon and beyond.

3/6

Family trees allow family histories to be depicted in all of their uniqueness; at the same time, they offer a pattern, in which all families can inscribe themselves. A few key data make up these documents: founding names and dates are the basis while marriage(s) and descendants guarantee the family’s continuity into the next generations.

Genealogy is pimarily a family affair. Tailored for the urban patriciate and available as data, family trees nonetheless provide more general insights as well.

Available as data, family trees can also be evaluated in terms of social history. In addition to dates and names of a family’s descendants, the marriages between the Basel council families are shown here as a word cloud. The size of a name indicates the frequency of marriages with the Faesch family. The visualisation is based on over 400 marriages concluded with the Faeschs between 1530 and 1929. In addition to marriages within their own family, the Faeschs were statistically primarily associated with the Becks, Burckhardts, and Bischoffs.

4/6

For instance, the data can be narrowed down in time, i.e. to the 17th century; it can also be differentiated according to gender. This makes it possible to describe more precisely which council families the Faesch were associated with at that time – and also to show the differences and similarities in the marriages of daughters and sons.

It is again striking which names stand out. For all marriages in the 17th century: Burckhardt, Beck, Bischoff, Huber, Stähelin, and Merian; for the daughters' marriages: Socin, Huber, Rhyner, Beck, Battier, and Forcart; and for the sons' marriages: Bischoff, Werenfels, Beck, and Burckhardt. Certainly no definitive conclusions can be drawn from such at list, but at least hypotheses can be formed. One can for example assume that the council families liked to keep to themselves. But there are also deviations from this – or rather, this statement does not always apply equally. In the choice of partners of the Faesch family in the 17th century, for example, one looks in vain for the name Faesch. The practice of marrying within one's own family seems to have been adopted by the family only from the 18th century onwards, and then repeatedly. This is quite unusual for patrician families in Basel and would need to be investigated in greater depth.

5/6

It would be logical to extend this data set to other patrician families in Basel. If we apply the same procedure to the Burckhardt, Beck, and Bischoff families (the most represented among Faesch's spouses) a rather similar picture emerges: most frequently, marriages are contracted with a few other families – as well as their own. The Burckhardt and Bischoff families, however, cultivated the practice of marrying within their own family as early as the 17th century.

Marriages ensured that the Daig remained largely among themselves.

The expansion of the Faesch family's data base to include the marriages of the Burckhardt, Beck, and Bischoff families could be easily extended; for Basel, the results of genealogical research on about 180 patrician families are available as freely accessible data (cf. www.stroux.org).

6/6

The concentration on several families, as demonstrated here, could be used to map a complete network. Ultimately, the marriages of about 180 families over the entire early modern period would be available as a database. This database could then be evaluated according to specific questions.

The quality of the data determines the possibilities of its evaluation.

The original interest in representing one's own family, its origins, and history as a family tree thus becomes the basis for a digital historiography. Family trees as sources of individual memory can be mapped as data with which patrician genealogies can be analysed as part of an urban familial network. It remains crucial to remember, however, that the quality of the data determines the complexity of the questions posed, as well as and the possibilities researchers have to evaluate the information itself.