From monasteries and libraries

1/9

In addition to the much larger stock of printed books, the Faesch Library also included manuscripts. The online catalogue of the university library now shows approximately 250 objects tagged with the note "Previous owner Museum Faesch"; this corresponds - as with the printed books - to only part of the original holdings – it reflects what is currently available digitally.

250 handwritten documents from 1000 years! What now?

An initial review of the manuscripts reveals a heterogeneous corpus of texts that can nevertheless be evaluated according to certain criteria. The manuscripts can be assigned to different genres; a present-day structure would look something like this:

- medieval manuscripts

- Correspondence

- Working papers

- Family writings

- Miscellaneous

2/9

Remigius Faesch himself arranged his library according to a different pattern. He simply assigned it to the four subjects according to which the universities of the time organised knowledge and research: the faculties of theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and the liberal arts. He used this logic to compile a catalogue of the library he began in 1628; a second criterion for Faesch was the format, or size, of his books.

How was a library of 5,000 volumes organised in the 17th century?

This allowed for the most efficient, space-saving arrangement in the library room itself. Each of the subjects, thus, began in the catalogue with large-format folios and ended with the smaller octavo or duodecimal formats, i.e. with books in which one printed page (folio) was divided into either eight or twelve pages folded together.

The division into four subjects (faculties) arranged by scale was apparently sufficient to keep a collection of about 5,000 books in order. Only the faculty of the arts (i.e. the Artes liberales or liberal arts) was divided into further categories (Historici, Politici, Antiquitates, etc.) – which were all quite small.

3/9

If we use this classification scheme for the inventory of manuscripts which we can survey today, it becomes clear why the more detailed distribution of the liberal arts was sensible, even necessary. The largest share of the manuscripts (65%) were written by authors connected to the Faculty of Arts, about topics related to the arts.

It is methodologically problematic, however, to attempt to build a precise picture of the entire library on the basis of such data; its precision is reduced to the manuscripts whose presence in the library collection can be attested to. Extrapolations based on incomplete data are extremely unreliable. Nevertheless, as data they can point beyond themselves if we can correlate them to other data – something that we can do with a methodologically clear conscience.

4/9

The manuscripts can, thus, be compared to the old library catalogue, for example. This catalogue provides quantitative information on the library as a whole, including the number of pages per subject in the catalogue holdings.

The relations between the four subjects in the two data sets are surprisingly similar. As for the manuscripts, the books from the Faculty of Arts make up by far the largest part of the catalogue (68%). The most striking difference can be seen in the extent of theological versus legal literature. While theology accounts for just under 6% of the manuscripts, it takes up almost three times as much space in the catalogue. Conversely, the share of theological books in the manuscripts is a good quarter (26%), while it accounts for half of the catalogue of manuscripts.

5/9

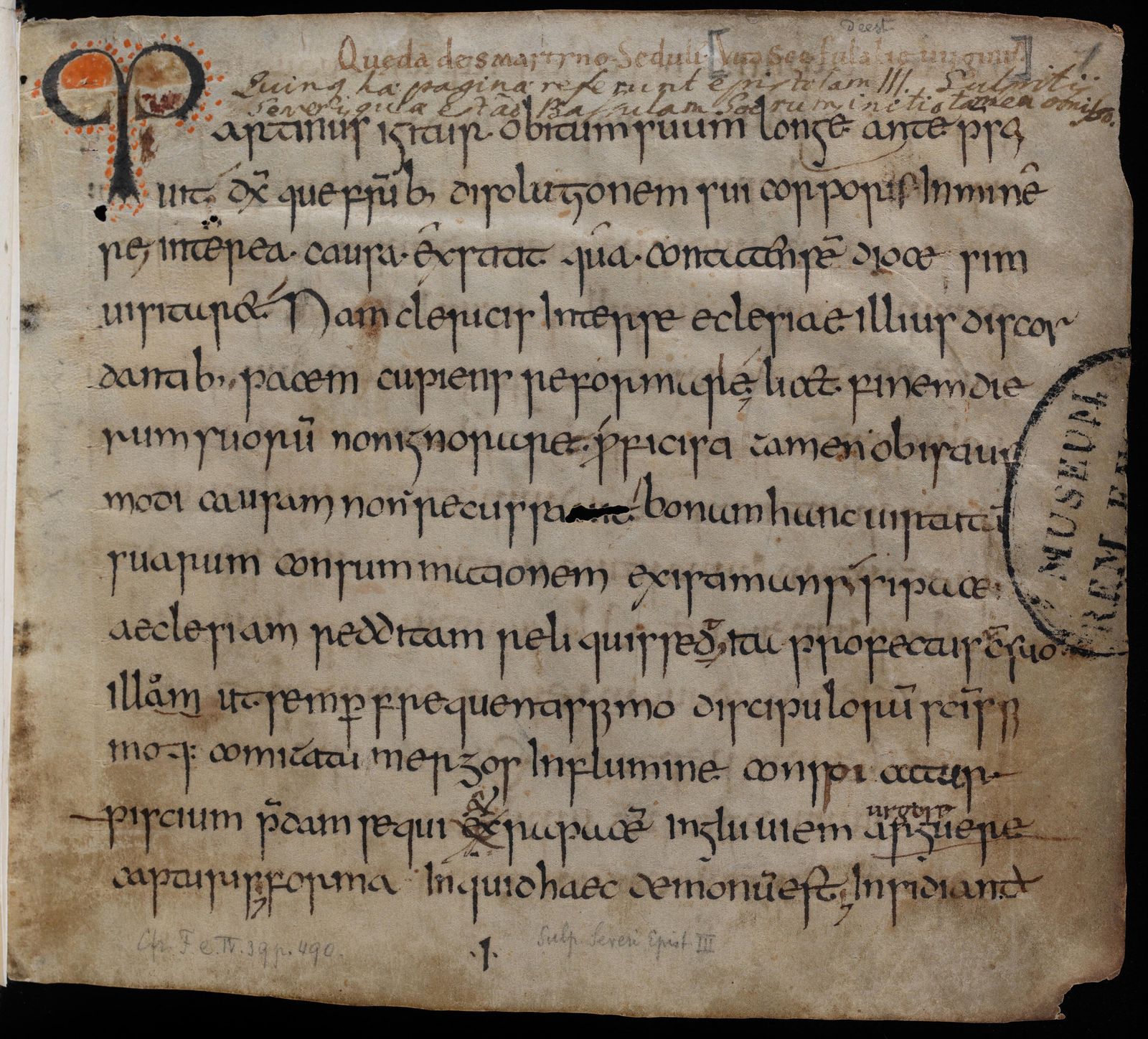

This observation leads to the structure and provenance of the manuscript collection. A classification according to the time of origin offers an explanation. Sixty manuscripts were written before 1400; among them are only one legal and two medical texts. Again, most of the texts deal with topics of the Faculty of Arts, but over 40% are theological in content. This is mainly due to the fact that Faesch acquired the medieval manuscript collections from monastery libraries, where books with theological content were naturally disproportionately represented.

6/9

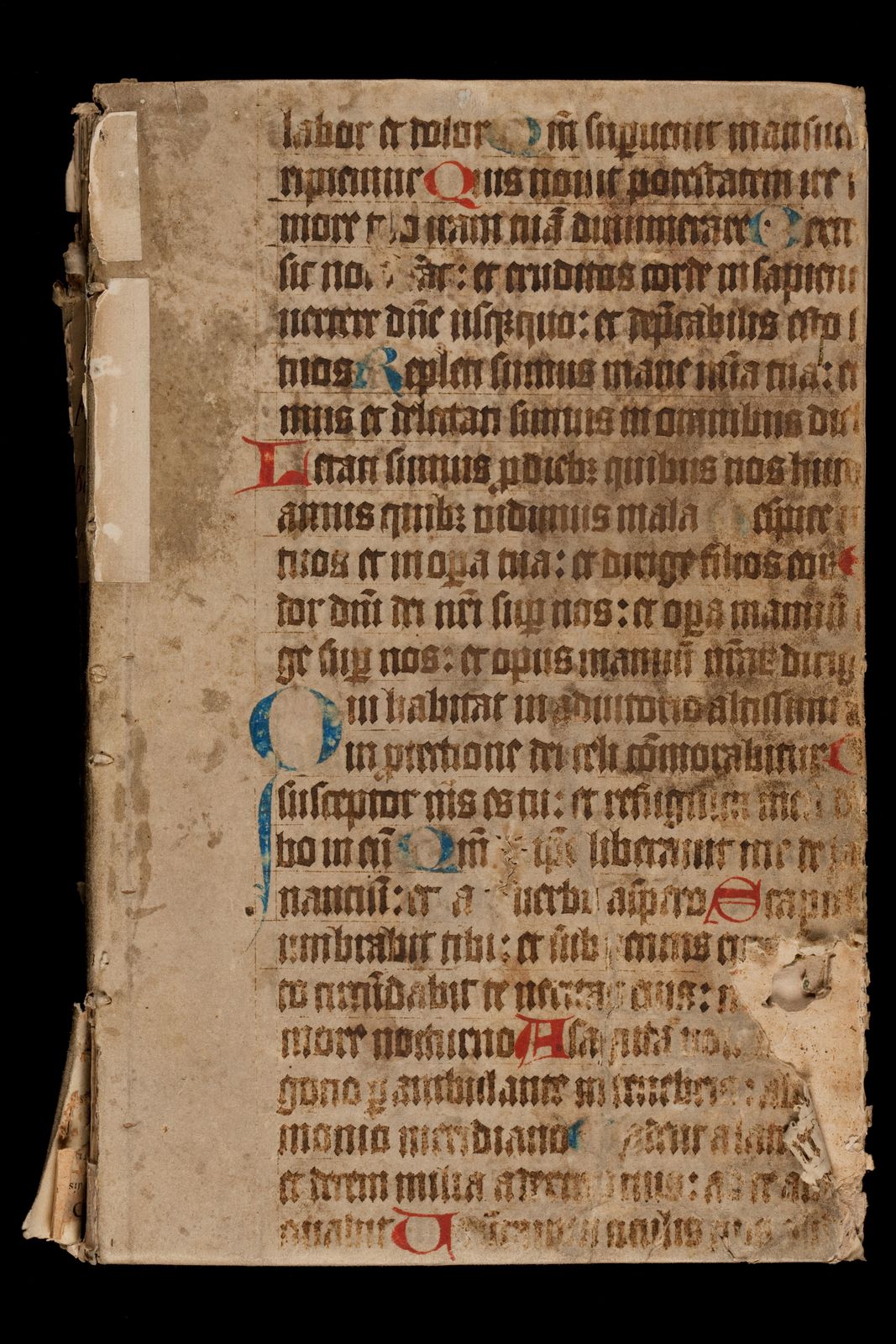

Over the following three centuries, the proportion of theological writings in the manuscripts steadily decreases in relation to literature on the arts. Several observations can be made that lead to this result. Faesch collected medieval manuscripts which he obtained from monasteries and which thus included a high proportion of theological writings. In the production of manuscripts from the 15th century onwards, however, the proportion of non-theological texts increased overall; this trend continued in the 16th and 17th centuries as is affirmed by Faesch's own output. At the same time, from the 16th century onwards, ongoing theological debates were increasingly conducted through the medium of the printed book. Finally, the confessional division following the Reformation may also have had an influence on the manuscript collection. Emblematic of this is Faesch's library catalogue itself, for whose cover a medieval Psalter was used. Deprived of its function as a liturgical book, it still served a bookbinder as a robust material.

7/9

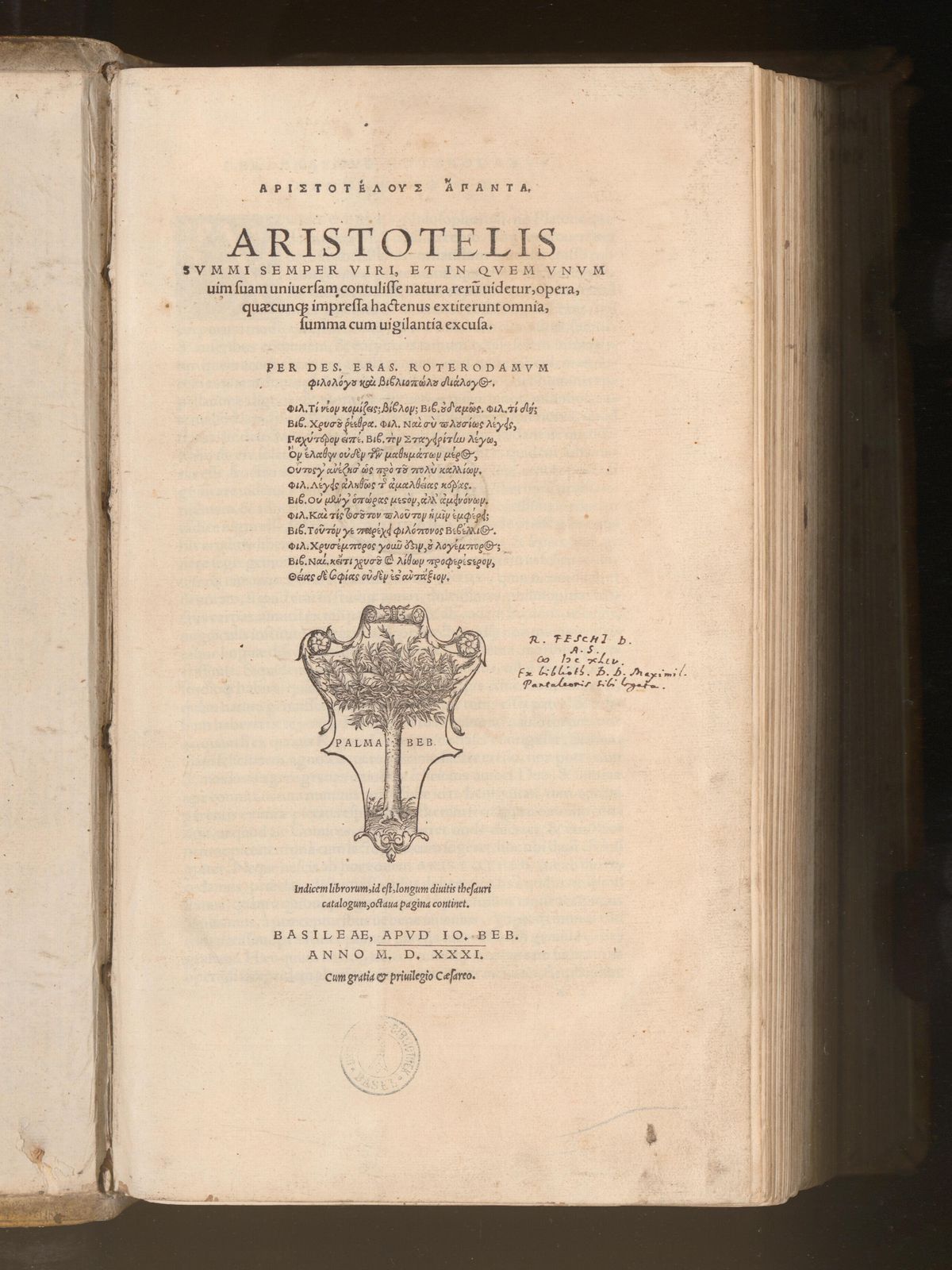

A different view of the manuscript collection is provided by a breakdown according to language. Latin is dominant, and this is true for every chronological period – from the early medieval tradition to around 1700. Greek, as the second 'old language', is also represented from the beginning, but dies out to a certain extent in the 17th century; while the modern languages, namely German, French, and Italian, increase.

Which topics, which languages can be found in the manuscripts of the Faesch Library?

All of this is hardly surprising and is connected to general trends in the use of language and writing in the scholarly circles of the early modern period. Remigius Faesch himself, for example, used Latin not only for scientific texts but also for the account of his trip to Italy; he also corresponded in French and, of course, German.

8/9

A look at the language distribution of the printed books in the Faesch Museum, however, adds another dimension to the purely quantitative findings. Two things are striking in this respect. Firstly, Hebrew only found its way into the library with 16th century printing; secondly, the disappearance of Greek from the manuscripts is offset by a considerable increase in printed books. Both are closely linked to Basel's importance as a printing city, where these two languages, important for humanism, were used in book printing at an international level. In fact, all seven books printed in Hebrew in the Faesch Library originate from Basel workshops.

9/9

Although the data available for the manuscript collection cannot be considered to be complete, certain observations can nonetheless be made.

With the printing press, Greek and Hebrew not only found their way back into the books, but also to Basel.

These do not provide conclusive results. They remain largely hypotheses and thought experiments; at the same time, they do form the basis for further research questions. The data can also be correlated with other (data)sets and subsequently linked to larger research contexts